The disciplines I am currently most interested in are art, literature and lens-based media.

Starting Points

Art

- Colour

- Form

- Line

- Point

- Scale

- Shape

- Space

- Texture

Lens-based Media

- Angle

- Composition

- Contrast

- Distance

- Editing

- Framing

- Mise-en-scène

- Viewpoint

Literature

- Alliteration

- Assonance

- Character

- Dialogue

- Imagery

- Metaphor

- Narrator

- Plot

- Similie

The above are all terms given to us in the course guide. There are some that are interchangeable across disciplines, but none have been repeated. There will be other terms added in my glossary.

Art

Colour

Colour theory as a topic is huge in art. The definition of colour is that it is produced when light hits an object and is reflected back to the eye. The wavelength that is reflected back to the eye determines which colour our brain sees. However, there are many subjective elements to it too. Colours evoke memories to us, they can be seen as warm or cool, some colours complement each other, some have cultural associations.

The Colour Wheel

There are 12 sections on the standard colour wheel. The three primary colours of red, blue and yellow; the three secondary colours are made from the primary: orange, purple and green; finally the six tertiary colours are made from mixing the secondary colours.

The wheel can also be split into warm colours and cool colours. Warm colours are the upper right half and are the colours that seem to be brought forward in a composition. Cool colours on the other hand are the lower left and seem to sink backwards in paintings.

Harmonious colours are those next to each other on the colour wheel, they work together well and seem to be pleasing to view. Contrasting or complementary colours on the other hand are opposite on the wheel and often clash and can create drama when together.

There are three other characteristics of colour:

- Hue: the colour itself, the distinctive quality by which one can distinguish one colour from another, e.g., red, blue, green, blue.

- Value: the brightness of the hue, the quality by which one distinguishes a light colour from a dark one, in the range from white to black.

- Chroma or intensity: the quality that distinguishes a strong colour from a weak one, the departure of a colour sensation from that of white or gray, the intensity of a colour hue.

Colours and Emotions

Choices of colour and the relationships between colours have a huge influence on how a piece of art or design looks and feels and the emotions it provokes. Colours have wider social and cultural meanings behind them too which can be used by an artist. For example, red has many different meanings. Often we link red to danger. In western culture, red is often used as a warning sign or to tell you to not do something. In traffic lights, the colour red is used to mean stop. Red can also have a link to anger. Cartoons or movies may show a character going red in the face when getting upset. It can also mean embarrassment. Red can also have positive associations. We link red with love and passion – it appears all over Valentine’s cards in February. We also see red as a festive colour – the colour of Christmas and Santa Claus. Different cultures treat colours very differently, however. In China, red is seen as a lucky colour. In South Africa, red is seen as the colour of death and mourning (which is normally associated with black in the United Kingdom). The use and meaning of colour can vary depending on where artists and their audiences come from.

Form

Form describes three-dimensional objects. It can describe how a sculpture forms a three-dimensional object in space. Form can also describe the illusion of how three-dimensional form is conveyed through the use of lighting and shadows, and the rendering of value and tone. Two-dimensional work can suggest three-dimensional objects by including implied forms. This means that lines or shapes are shown in a way that suggests they have depth. This can be done using perspective or through tone or colour effects.

Form can be either geometric or organic. Geometric is mathematical objects such as cubes, pyramids and spheres, they give a man-made appearance and can suggest solidity, balance and permanence. Organic forms look natural. They are irregular and may seem flowing and unpredictable. The most obvious example of organic forms is realistic representations of the natural world or living things, but they do not have to be realistic to be organic. Some designs combine geometric and organic forms.

Forms have mass. The mass of a form is a result of its size and the material it is made from. The greater the mass the heavier a form is. The appearance of an object can change how heavy it looks – its perceived mass. For example, darker and more intense colours or more detailed textures tend to appear heavier.

Line

Line is considered by many to be the most basic element of art. In terms of art, a line is considered “a moving dot”. Line has an endless number of uses in the creation of both drawings and paintings. Although we typically associate line with drawing, it’s also foundational to painting as they reveal the artist’s techniques.

Perhaps the most obvious use of line is when it is used to define the edges or boundaries of a subject. We can obviously communicate a subject’s edges by using lines. In most cases, when we begin a drawing, we start by drawing the outlines of the subject. The outlines are just the beginning since the line is also used to describe the details on the subject as well. Usually, we can simplify areas of contrast on a subject into a line.

Line can also suggest movement, mood, emotions and ideas.

Orientation refers to the direction of lines. They could be vertical, horizontal or diagonal. Lines can be used in art and design to help guide your eye around a painting or to create a sense of balance and structure. Deliberate use of horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines can help to create a focal point. They can also help to suggest depth and a sense of perspective.

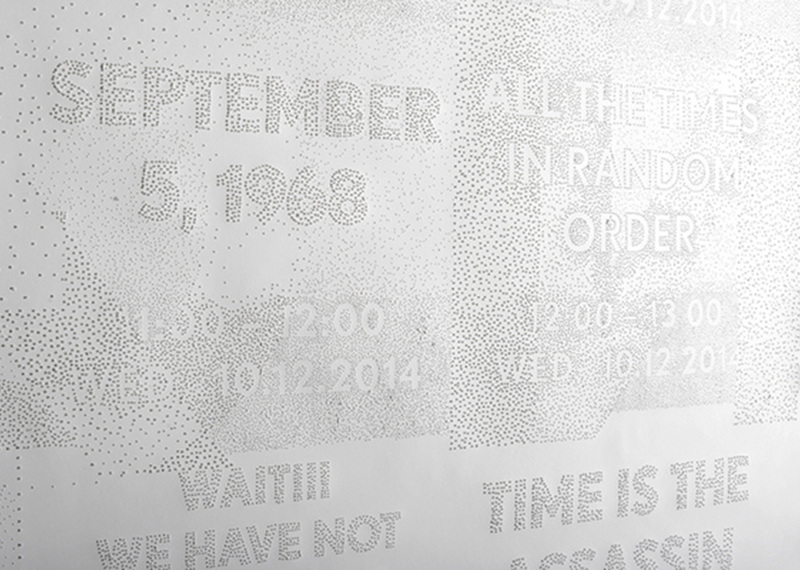

Point

Point can refer to the focal point of a piece of work. It is a key point of interest in your painting that you want to direct attention towards. It should be your most interesting point in the painting. It is possible to have more than one focal point but there is usually one strong point where the focus and attention is.

Scale

In art and design, the principle of scale refers to the relative size of one object compared to another, typically the size of the artwork to the viewer’s body. Scale can also refer to the size relationships of different visuals within a singular piece of art.

Shape

In the study of art, a shape is an enclosed space, a bounded two-dimensional form that has both length and width. Shapes are one of the seven elements of art, the building blocks that artists use to create images on canvas and in our minds. A shape’s boundaries are defined by other elements of art such as lines, values, colours, and textures; and by adding value you can turn a shape into an illusion of its three-dimensional cousin, form. As an artist or someone who appreciates art, it’s important to fully understand how shapes are used.

Like with form, shapes can be geometric or organic.

Space

Space, as one of the classic seven elements of art, refers to the distances or areas around, between, and within components of a piece. Space can be positive or negative, open or closed, shallow or deep, real or implied, and two-dimensional or three-dimensional. Three-dimensional work creates real space. Two-dimensional works can create implied space using various techniques.

Texture

Texture is used to describe the way a three-dimensional work actually feels when touched. In two-dimensional work, such as painting, it may refer to the visual “feel” of a piece. Many artists use texture to show their technique and to express emotion.

Tone and Value

As an element of art, tone or value refers to the visible lightness or darkness of a colour. Tones could refer to black, white and grey tones between. It could refer to how light or dark a colour appears. In real life, the tone is created by the way light falls on an object.

Two-dimensional artworks cannot show real form. The illusion of form can be created by using different tones that suggest different amounts of light hitting the subjects shown. This can fool the eye into seeing a three-dimensional object.

Tone can be used to create an atmosphere in art and design work. Different atmospheres will be created depending on the value and contrast of the tones used. A small amount of contrast tends to result in a calmer image, whereas high contrast creates drama. The term chiaroscuro is used to describe images with very high contrast.

Tone can also indicate depth and distance in artwork and artists can create focal points at different places in their work.

Lens-based media

Angle

Camera angles, and the degree of those angles, can totally change the meaning of a shot.

Eye-level shots

In an eye-level shot, the camera is positioned at the same level as the actors’ faces which gives it a sense of immediacy and realism. In everyday life, we see most other people at eye level and this shot type is often used when filmmakers want us to feel part of a scene.

Low-angle shots

Using a low angle shot is an effective way to establish a character’s importance in a scene as they make characters look powerful and imposing.

High-angle shots

Here the camera is above the object or actor being filmed and is pointed down at them. High angle shots make characters and objects seem smaller. High angles can also work to make characters seem weaker or more vulnerable.

Worm’s eye view

This is an extreme low-angle shot in which the camera is very far below the subject and pointed upwards. This angle exaggerates the scale of the shot’s subject and can make actors seem like imposing giants.

Bird’s eye view

Sometimes called an overhead shot, this camera angle places us directly above the subject. The Bird’s eye view can be used to show us action that might not be visible from eye level.

Dutch angle

For a Dutch angle, the camera is slanted to one side. With the horizon lines tilted in this way, you can create a sense of disorientation, a de-stabilized mental state, or increase the tension.

Composition

Composition is important in photography and art. It links to viewpoint and framing and it is also important to consider the other formal elements of art such as line, shape and balance. Composition refers to the positioning or arrangement of people, objects and landscapes in the frame. Good composition can enhance the meaning of an image.

Leading lines are a useful compositional tool. A viewer’s eyes tend to look for lines and follow them from one end to the other. The effect is particularly strong when different lines come together.

Contrast

Contrast can mean many things in photography and film.

One way to add interesting contrast is to use sections of black and white. Working in black and white can draw attention to light and tones, shapes and textures.

Editing

Editing can be done in both film and photography. A well-crafted edit can create meaning and take audiences on emotional journeys. Simple editing of photographs can include cropping the image or removing errors and minor blemishes like dust spots. Underexposed areas can be lightened and washed out areas can be made to appear darker. This can be done quickly and easily. It is also possible to make more significant changes to an image. This can be used for artistic or experimental effects. For example, you might change the contrast, increase or decrease colour saturation, add blurring or mix areas of black and white and colour.

In film, at its simplest editing can remove bad takes and shorten sequences, but when filmmakers fully harness its power they can create meaning where none existed and take audiences on emotional journeys.

Continuity editing

The most common form of editing is continuity editing. In this editing style, shots from different angles are cut together to create a sense of continuous movement and continuity. This creates the impression that time and space remain consistent within the scene, even if the shots have been filmed at different times. A key aim of this style is to ensure that no single cut calls attention to itself and that nothing strikes the viewer as confusing or inconsistent. When continuity editing is applied correctly we may not notice the individual cuts.

Montage editing

The main alternative to continuity editing is montage editing. Montage editing can be used to create excitement, terror or startling new meanings. Instead of allowing shots to flow smoothly from one to another, montage editing juxtaposes images for effect and can cut rapidly from wide shots to extreme close-ups. Montage editing draws attention to itself in ways continuity editing does not.

Other editing techniques

Cross Cutting

This is used to cut between two different actions happening at the same time. By cutting back and forth between these different events, the director can establish that they are somehow linked.

Freeze Frame

This highlights an important moment by creating a pause effect in which a single frame of film is extended for several seconds.

Slow motion

These effects are usually captured by the camera by changing the filming speed but can also be achieved in post-production by slowing individual shots down. This can help emphasise special moments or draw out actions to generate suspense.

Distance and Framing

Framing a camera shot can make audiences feel more connected to the story you are telling. You can alter the frame by placing the camera closer or further away from the action being filmed.

Close up

A close-up shot shows us a character or object at close range. A director might choose to show an actor in a close-up so that the audience can properly see their face. This allows viewers to see the character’s facial expressions and gives them a clue as to how the character is feeling emotionally. A director might also use a close-up of an object so that we can see its importance. Extreme close-ups can be used to build tension or add extra emotion to a scene.

Medium shot

A medium shot, sometimes called a mid-shot, is a shot taken from the middle distance. A medium shot of an actor won’t show us their face in the same level of detail as a close-up but it will let us see more of their body and surroundings. Medium shots of actors are often framed from the waist upwards and that combination of distance and framing allows us to see both a character’s face and their body language.

Long shot

A long shot, sometimes also known as a wide shot, takes us far away from the character being framed. This gives the audience much more information about the scene in general and puts the actor in context, as we usually see them in the middle of a landscape or busy environment.

Thinking about where objects and people are in the frame itself is crucial. If a character is important in a scene, a shot might place them in the centre of the frame. If two characters are drifting apart, one way to show that might be to position them at opposite ends of the frame. One specific tool film-makers sometimes use to help with framing is the Rule of Thirds. The Rule of Thirds is an approach to framing which divides the frame into three sections across the horizontal and vertical lines. Placing actors, edges of objects or the line of the horizon on these imaginary lines makes it easier to create balanced and pleasant compositions.

Mise-en-scène

Mise-en-scène is how all the aspects of a film combine to create a convincing world on screen. It involves everything you can see on a screen or in an image including props, costumes, make-up, location, set, performance and animation.

Viewpoint

Viewpoint links to composition and angles. The distance your subject is to the camera can change how much of the frame it fills, how its scale compares to its surroundings and how flat or deep the image will appear.

Directors can also change the viewpoint by moving the camera during filming a sequence.

Pans

In a panning shot, or pan, the camera is locked onto a tripod and the tripod is fixed in one spot. The tripod head, which the camera rests on, is pivoted from left to right or right to left. The effect is much like standing in one place and looking from side to side. Panning is often used to follow action such as a character moving from one spot to another. Panning shots can also be used to establish locations, slowly revealing information about a place as we take it in.

Tilts

A tilt is similar to a pan in that the camera is also fixed to a tripod. However, instead of pivoting from left to right, the camera is tilted up or down. Tilts can be used to follow the action. If a character on screen was climbing a ladder, the director might use a low angled tilt to follow them as they move upwards. Tilts can also be used to tell us a little bit more about a location than a single, static shot might.

Tracking shot

In a tracking shot, the camera is placed on a moving platform or vehicle so that we can follow alongside the action. Nowadays, tracking shots can also be achieved by using Steadicams. A Steadicam is a self-balancing camera rig that is attached by a harness to the camera operator. When a Steadicam operator moves, the camera moves with them creating a smooth gliding motion.

Handheld camera

In a handheld shot, the camera is carried by the camera operator. Because this technique gives scenes a bumpy and unpolished feeling it is often used by directors when they want viewers to feel embedded in the action of a scene.

Crane shots

In a crane shot, the camera is mounted to a crane and can move up or down. Crane shots are usually used for dramatic effect, making us feel as if we are swooping over a location or diving down from above.

Zoom shots

A shot that uses the zoom lens to suddenly push us closer to or further away from a subject is called a zoom. Zooms can be effective if used creatively but can also seem amateurish and distracting if overused.

Aerial shots

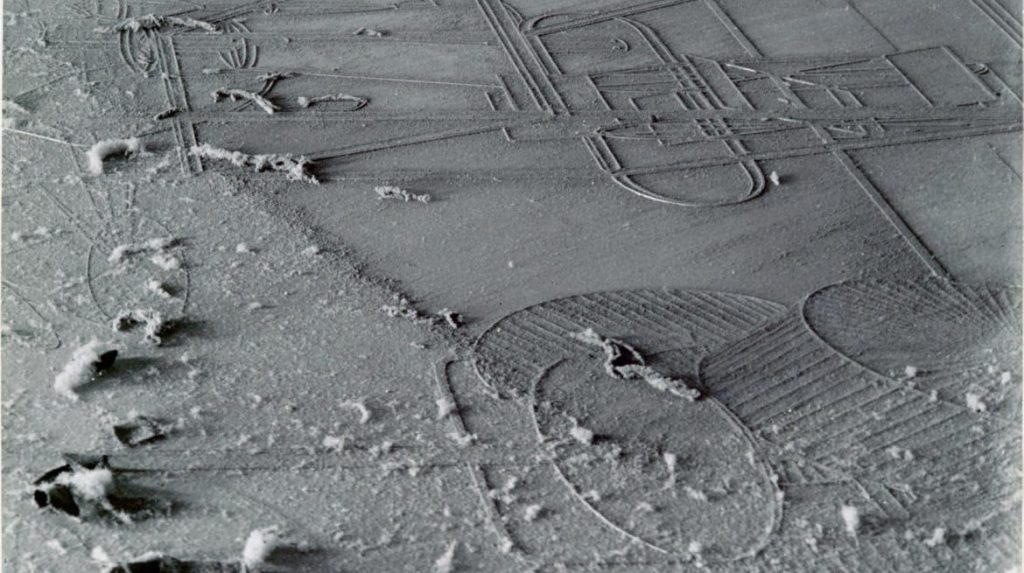

In an aerial shot, the camera is mounted to a flying vehicle and flown over the action or location. Aerial shots are often used at the start of a film to establish the setting and create a sense of mood.

Literature

Alliteration

Alliteration is when words start with the same letter and, more importantly, the same sound. It can be used to create a mood or for emphasis. Alliteration can build a mood or set the scene depending on the letters that are used:

- The gentle ‘w’ sounds in “whispering wind” create a soft and airy mood.

- The harsh ‘r’ sounds in “raging river rapids” help the reader to imagine the brute force of the water.

Alliteration can also be used to capture the reader’s attention and reinforce a point.

Assonance

Assonance is a technique similar to alliteration but where the same vowel sound repeats in a group of words. For example, “It beats . . . as it sweeps . . . as it cleans!”

Assonance is a method of achieving emphasis and cohesion in a short stretch of text.

Character

Characters in texts are developed through what they say and do, and the language used to describe them. There is explicit characterisation and implied characterisation. The character is built up through description, dialogue, how other characters see them, behaviourisms.

Characters usually change over the course of a text. These changes can be a powerful way to present themes and important ideas to the reader. As the text continues, the author often adds more details to the picture of a character. How the reader reacts to a character can be very important to how they feel about the text. There should be contrasts or contradictions – not just between characters, but within each character. In real life, no one is simply good or bad. All effective characters have more than one side.

Dialogue

Dialogue is a conversation between two or more characters in a literary work. It could also be an inner dialogue which is a character’s internal voice. Dialogue is essential for several reasons. First, it creates characterisation. In fact, it is one of the four main methods of characterisation. The audience learns much about a character through his speech. Second, dialogue advances the plot. Interactions within, between, or among characters help to give insight into the storyline. Additionally, well-written dialogue makes a text realistic. In the real world, people interact and have conversations. This is critical to a successful text.

Imagery

Imagery is the use of language and symbolism in writing which make our five senses active. The word ‘imagery’ gives rise to the creation of mental images and figures. The imagery brings to life the characters of the story through the mental pictures of the readers. These are effective devices used by the authors to create these effects.

Visual

Visual imagery is the one where the author uses various visual qualities to create imagery. This can include various shapes, sizes, colours, lights, shadows, and patterns. This is the most common form of imagery that is used in literature. Whenever the term imagery is used people understand visual imagery in literature. They generally use metaphor and simile to create visual imagery.

Auditory

Auditory Imagery creates an appeal to the reader’s sense of hearing. Creating auditory imagery through writing is not that easy. For instance, creating imageries by author by creating sounds of war in a war novel. Onomatopoeia is mostly used by authors to create auditory imagery.

Gustatory and Olfactory

Gustatory imagery is the one that appeals to the taste of the readers. This is generally used to depict the food as the character eats it. This may create a sense of gustatory imagery when the readers read about a portion of food. Olfactory Imagery is the imagery when the author tries to attract the reader’s taste or smell. It helps in depicting the situation through which the characters of the narrative are going through or experiencing. The smell of fresh rain, the smell of fire are some of the examples of olfactory imagery.

Tactile

Tactile Imagery is the one that creates a sensory effect of touch through text or the writing of the authors. This is used to convey how some things feel when touched. It may be used to convey the sense of texture, temperature, wetness, dryness, and so on. They help in creating empathy for the characters in a narrative.

Kinaesthetic

Kinaesthetic Imagery is the one that is used to give a sense of motion by the author. Speed, slowness, falling, or even fighting can be depicted with the use of Kineasthetic imagery. Kinaesthetic imagery is very relevant in the era of action movies and screenplays. It also gives a good feel when needed to write about sports, driving, and other actions.

Organic

Organic Imagery is a type of imagery that appeals to the most traditional forms of our senses. They are the feeling of hunger, fatigue, fear, and even emotion. They form the basic tenets of human emotions. It moves the readers to the feelings of either joy or sadness. When they are written efficaciously creates intense sorrow and desperateness which the readers can feel immensely.

Metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that describes something by saying it is something else. It’s not actually true but it gives the reader a clearer idea of what it is like. For example, “They were peas in a pod.” Extended metaphors are metaphors that run throughout a piece of work.

Narrator

Voice means the tone of the narrative. Think about the language used in the narration and what that tells us. In some texts, the narrator is also a character. In others, the narrative voice is more distant. Narrative can be first-person – indicating a clear point of view – or third person – which could follow one character closely or take an omniscient standpoint.

Plot

The plot is the series of events that comprise a story’s main action. It is typically made up of a sequence of individual but connected elements that compels the main character(s) to embark on a journey. This journey can be physically or mentally and emotionally in nature, though it is often both. The plot’s primary journey leads to a climactic event and a resolution. Most plotlines follow the same basic structure made of five essential ingredients.

Exposition

A story begins by introducing the protagonist and other key characters, their inter- and intra-relationships, the setting, and relevant background information. In this section, the protagonist discovers their main goal, typically a problem that needs surmounting.

Rising action

The next phase is the rising action, which begins with an inciting incident or complication that triggers the ensuing series of events. Since the rising action propels the protagonist on their journey, the inciting incident usually comes with high stakes. Tension tends to build as rising action progresses toward the next phase.

Climax

This is the main turning point of the story when all the events and emotions built up during the exposition and rising action come to a head. Naturally, these are the moments of greatest tension, conflict, and drama.

Falling action

In this stage, the characters’ actions resolve the story’s central problem, leading to a resolution.

Denouement

The final plot element is the official completion of the goal, solution to the problem, an end to the conflict. The protagonist or the antagonist might win, or each could experience certain degrees of both triumph and defeat. Some stories wrap up by providing information on what happens to the central character(s) in the future.

Similie

A simile describes something by comparing it to something else, using like or as. A simile is a useful way to describe something without using a long list of adjectives. It can create a vivid image in the reader’s mind, helping to engage and absorb them.